Chera Kee is an Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies in the English Department at Wayne State University in Detroit, MI. Her research interests include zombie media and intertextuality in fan works.

Contact: [email protected]

Poe Dameron Hurts So Prettily: How Fandom Negotiates with Transmedia Characterization

by Chera Kee

Published December 2017

Abstract:

Charismatic Poe Dameron is the “best pilot in the Resistance,” and while his depiction in Star Wars: The Force Awakens (TFA) presents audiences with a confident, dashing Han Solo-type, that is not the end of the characterization. Transmedia TFA paratexts paint Dameron as not only dashing but also reckless and so devoted to the cause he’s willing to plunge headlong into danger for it. Furthermore, the film and these paratexutal tie-ins present Dameron as constantly in danger or in pain. In some fan works based on the film, particularly those in the hurt/comfort (h/c) genre, Poe Dameron just keeps getting hurt. While this might seem to be the kink of one particular fandom community, I argue that hurting Poe in fan works not only fills in missing information from the film, it also challenges Disney's characterization.

Kylo Ren (Adam Driver) uses the Force to interrogate Poe Dameron (Oscar Isaac) in Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015). Image screenshot from 00h 17m 54s.

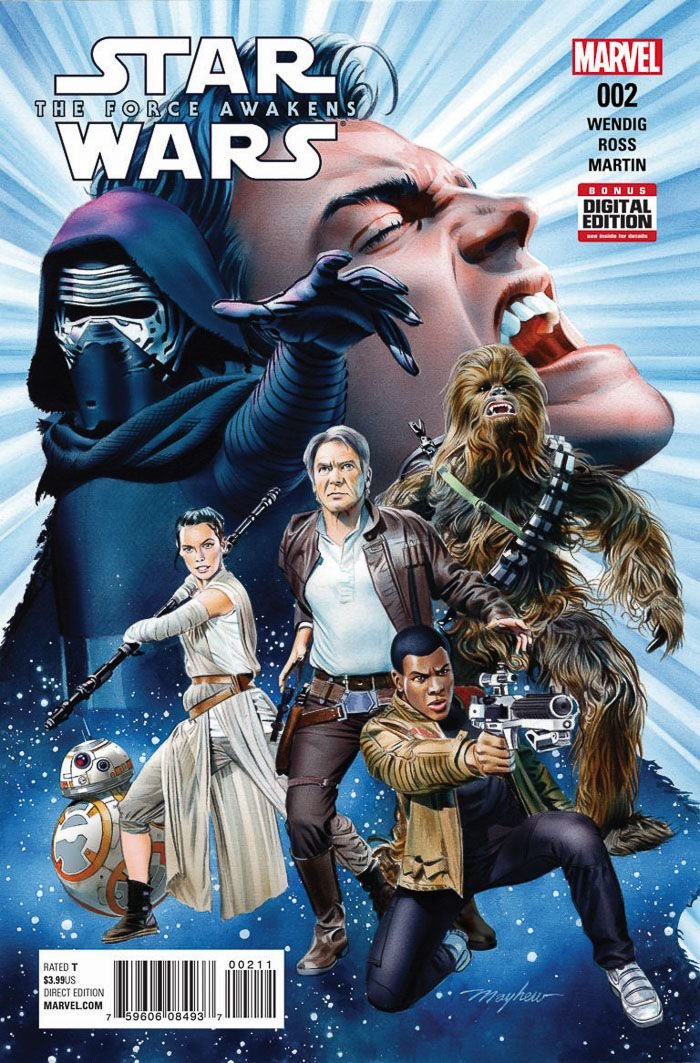

Marvel’s The Force Awakens, Part II comic book adaptation features Poe Dameron prominently in the upper right quadrant of the cover art by Mike Mayhew. Image of cover is from http://www.starwars.com/news/comic-book-galaxy-star-wars-the-force-awakens-2-and-more.

Early in Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015, TFA), the evil Force-user Kylo Ren tells us that Poe Dameron is “the best pilot in the Resistance,” and all the evidence from the film, as well as numerous transmedia extensions of it, affirms this. Poe flies circles around attacking TIE fighters in the skies over Takodana; he delivers the shots that will destroy Starkiller Base at the end of the film. In the making-of documentary, Secrets of The Force Awakens: A Cinematic Journey (2016), Lawrence Kasdan explains that Poe is envisioned as a sort of second-generation Han Solo—charismatic, perhaps a little cocky, but someone you’d want on your side. Of course, Poe’s daring exploits become even more remarkable when one learns that the character was originally slated to die early in the film but was saved when Oscar Isaac revealed his reluctance to take on the role for that very reason. One re-write later, and Poe lived to fly another day. Yet, in a narrative universe that is traditionally easy on the gore, Poe is also noteworthy as the only major character in TFA to sustain clearly visible wounds that linger, and some fan works based on the film take Poe’s bruises and run with them.

The genre of fan works called hurt/comfort (h/c) typically revolves around the physical or psychological pain of one character that becomes the catalyst for another to provide aid. Historically, while fan communities have been open to a wide array of representations and tropes, there are those areas of fandom typically considered darker than others, and while fans of h/c contend, among other things, that it becomes a fictional way to work through real-world issues, critics claim that it merely aestheticizes injury and torture. While the critics of h/c fan works that focus on Poe Dameron have laid out similar charges, hurting Poe in fan works may move beyond simply basking in the pain of a favorite character. It is, after all, backed up by canonical depictions of Poe from the TFA transmedia universe, including the Poe Dameron comic, the novelization of the film, and other tie-ins. Thus, what at first glance might appear to be highly transgressive behavior on the part of some fans could also be read as fans responding to a canon that already sets Poe up to be hurt; in many ways, these fans are simply continuing what Disney has already started. Hurting Poe—at least canonically—also works to reaffirm his place as the reckless soldier who needs to be tamed to become a true leader. Yet, in expanding Poe’s hurt in fan works—by emphasizing the very real physical and psychological consequences of his torture—fans may be both replicating and resisting Disney/Lucasfilm’s canonical characterization of Poe.

Hurt and Comfort

Hurt/comfort is one of the oldest genres of fan fiction and also one of the more divisive amongst fans. While there are many who see h/c as offering up a safe space to talk about real-world traumas, others see it as taking pleasure in character suffering. In fact, in her description of the genre in her 1992 book Enterprising Women, Camille Bacon-Smith notes, “As a researcher, I found hurt-comfort the most difficult form to study…and the [fan] community seemed to support my negative judgments about the genre” (255). As Fanlore.com explains, hurt/comfort developed out of “get” stories from the late 1960s and 1970s (“Hurt/Comfort”). By the late 1970s, these stories were simply called hurt/comfort (h/c), and as most early h/c stories did not have explicitly sexual elements to them, many have theorized that h/c acted (and may still act) to explore same-sex intimacy without having any sex. As one fan in 1981 speculated, one of the reasons the genre might have developed was because of “our social culture, where males are not supposed to show feelings, and homosexual relationships are frowned upon as unnatural and perverted. So, when is it acceptable to show emotions? Well, when someone is hurt” (qtd. in “Hurt/Comfort”).

One reason why some have taken issue with h/c is they see it as “punishing” same-sex pairs for loving each other (qtd. in “Hurt/Comfort”). Others are bothered by h/c writers’ seeming need to torture characters just to create a situation in which another character can provide comfort. In Enterprising Women, Bacon-Smith theorizes that the genre “is a complex symbol system for the expression of strong feelings that masculine culture defines as unacceptable” (270). Yet, some of these assumptions may seem a bit dated to today’s h/c fans. While nurturing may still code as feminine, there are plenty of examples of nurturing men in contemporary mainstream media; furthermore, while there are still examples of h/c that contains no sexual or romantic elements, there is also plenty of h/c that does, so the idea that the hurt/comfort dynamic might serve as a substitute for sex doesn’t fit the breadth of the genre as it exists today.

Much of the negative judgment of h/c comes from the misguided idea that it must be written by sadists, but even fans of the genre are often apologetic about liking it. As Rachel Linn notes in “Bodies in horrifying hurt/comfort fan fiction: Paying the toll,” some see “finding pleasure in a character suffering” as “morally dubious or maybe even evil” (1.4). Yet, scholars and fans of h/c list myriad reasons why some might be attracted to the genre. Lucy Gillam explains, “Women are socialized to be caregivers. We like guys who need us, whom we can take care of. At the same time, we want men who are strong, capable, etc. How to reconcile these two contradictory desires? Take a strong, capable man, and hurt ‘im….”

In “H/c and me: An autoethnographic account of a troubled love affair,” Judith May Fathallah contends h/c allows writers and readers to explore being made vulnerable—though a beloved character—without having to be made vulnerable in real life (3.1). As she suggests, “Perhaps h/c taps a fantasy: the empathetic, nontransmittable understanding of pain” (3.2). Sarah Fiona Winters proposes a more metatextual approach: “Putting a character through pain and suffering is one way to examine exactly what he is made of…it reveals the emotional and vulnerable dimension to that character that canon insists on hiding or denying. In their analytical function, fan works (to paraphrase Wordsworth) torture to dissect” (3.10). Yet, for all the possible reasons why some fans may be attracted to the genre, Fathallah warns against trying to find “a totalizing theory of h/c” as each fan brings a different social and personal history and set of needs to the table when it comes to the genre (3.7).

Linn suggests the discomfort both fans and critics of h/c feel about the genre “does not stem from the presence of pain itself but from a certain kind of pain prevalent in h/c” and she believes “it is the excessive emphasis on bodies, especially bodies in pain, that drives these anxieties” (1.4). It is the emphasis on the body—in particular, the evidence left on the body after torture—that is compelling in terms of Poe Dameron, namely because it is this bodily evidence that some fans have pointed to as spurring on their need to hurt Poe in fan works. Thus, another reason why some fans turn to h/c: its mirroring of canonical source material. For instance, fan Renae is quick to point out that h/c finds its roots in mainstream media: putting characters in peril is a ploy many television shows and films use to “draw the viewers” in (“Hurt/Comfort: a Confession and a Celebration”). Bacon-Smith echoes this in her analysis, where she notes that fans may draw on canonical instances of torture, threat, and injury in crafting h/c works (257-8). Thus, whether one finds it abhorrent or therapeutic, there is evidence to suggest that h/c often takes from what is already present.

Canonically Hurt Poe

But just how do canonical depictions of Poe Dameron feed h/c works? The 2015 novelization of TFA by Alan Dean Foster describes Poe as being “a bit proud of countenance: something that others, not knowing him, might mistake for arrogance. Confident in his skills and in his mission, he sometimes displayed an impatience that arose only from a desire to fulfill the task at hand” (13). In other canonical works, Poe’s “impatience” becomes outright recklessness—but recklessness in devotion to his cause. The first issue of the Poe Dameron comic, which is set in the time immediately preceding TFA, opens with Poe trying to navigate a crumbling cave system in his X-wing, assuring his astromech droid BB-8 as they attempt to fly through a closing doorway, “We can do this! Probably!” (Soule 8). In Before the Awakening, Poe nearly breaks his neck on a mission and spares “an instant to thank whoever or whatever it was that watched out for reckless, foolish pilots” (Rucka 197). Michael Kogge’s children’s book, Poe Dameron: Flight Log, describes Poe as a “loose cannon” (3), and Pablo Hildago’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens: The Visual Dictionary’s entry on Dameron refers to him as “Reckless Poe” (12).

Yet, the entry also notes, Poe’s “appetite for risk is indulged by even the most serious minded Resistance commanders, as he gets spectacular results…Though brash, Poe has great charisma and limitless respect for the idealistic founders of the Resistance” (12). Poe’s utter devotion to the cause mitigates his recklessness in many of the TFA paratexts. In Before the Awakening, the reader learns, “if his mother had taught him to fly and to love it, his father had taught him that when you commit to doing something, you commit to going all the way or don’t do it at all” (158-9). The leader of the Resistance, General Leia Organa, sees this devotion; it’s why she recruits Poe in the first place, but there are hints throughout the transmedia universe that this devotion—especially when coupled with Poe’s recklessness—may get him injured or even killed.

In the Log Book, Poe reflects on getting captured on Jakku—the event that opens the film: “I didn’t care about my own life. What mattered were the map, General Organa, and the Resistance” (57). In Moving Target: A Princess Leia Adventure, the novel ends with Leia discussing Poe with another officer; she says, “I've never worried about Poe's commitment. My worry is for what that commitment may cost him” (qtd. in “Poe Dameron”). Thus, while the film may hint at Poe’s reckless nature—in his snarky attitude to Kylo Ren and his absolute glee in stealing a TIE fighter with ex-Stormtrooper Finn—the expanded Star Wars universe explicitly presents Poe as reckless and so devoted to the cause as to be willing to plunge himself into danger for it.

In TFA, this leads to his capture by Kylo Ren. Soon after, Ren interrogates Poe, and this scene is important when considering why some fans may enjoy h/c works focused on Poe. The scene begins with a close-up of Poe’s face. He’s lit from above, surrounded by darkness—as if he is in spotlight. There is blood on his left temple; his lip is bleeding. Whatever physical torture has happened, it is over, but the camera is close enough and the light so focused on Poe, that it is nearly impossible not to catalogue Poe’s injuries. The scene eventually cuts to a long shot with Poe on the left side of the frame and Ren on the right. Yet, many of the shots in the scene are medium or close-up shots, mainly centered on Poe’s face and Ren’s mask or gloved hand. The comic book adaptation of the film mimics this close framing of Poe. In issue #1 of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the interrogation scene takes up one page. The first panel is the exterior of the ship the Finalizer. The second shows Kylo Ren on the left and Poe strapped into the interrogation chair on the right. The third panel is Kylo’s outstretched hand, with Poe’s face contorted in pain, and the final portion of the page is taken up by three close-up panels of Poe’s face, each moving successively closer (Wendig). In both versions of the scene, Poe’s torture is handled intimately, in close quarters, making it nearly impossible not to see the physical damage to Poe’s face.

Fans were quick to note the erotics of Kylo Ren’s Force-enhanced interrogation of Poe. At one point, after Ren has begun using the Force on Poe, there is a cut to a side view of Poe as his head slams into the interrogation chair. Poe then arches back as his throat is exposed. He closes his eyes, moaning. More than one fan has mentioned the suggestive nature of Poe’s reaction here, as in this series of notes on a tumblr post of a gif of the shot that mention, among other things, “in my mind, it was not a ‘torture’ [t]hat he was receiving at the time…” or “that gasp” (@artisfaction). Certainly, without the framing context or the soundtrack, Poe could be writhing in pleasure. The romantic undertones of the sequence are also hinted at in the novelization, where, as Stormtroopers take Poe away on Jakku, the reader learns: “[Kylo] Ren watched them for a moment, contemplating possibilities. Later, he told himself” (23). The phrasing suggests Ren is fantasizing about Poe’s torture in a way that further blurs the lines between pain and pleasure.

In discussing the torture of Daniel Craig’s James Bond in 2006’s Casino Royale, Tim Edwards notes the homoerotic overtones of the scene, which are “increased by the lighting of Craig’s body which although bruised and bloody in places, literally gleams with phallic virility” (175). Likewise, Drew Ayers observes that 1980s action films “take much pleasure” in scenes where the hero is tortured, which “have their roots in traditional Christian iconography of passion and suffering” where “the endurance of pain indicates a triumph of spirit over body” (44). While there may not be a deliberate attempt on the part of the filmmakers to link Poe to Christian iconography or action heroes, the image of a beautiful man suffering resonates nonetheless—yet unlike the 1980s action heroes or James Bond, Poe breaks under pressure, mitigating the sense that his pain is virile or triumphant.

But that may be the point: Poe’s pain becomes something of a trademark for the character. In the film, even after Poe has ostensibly cleaned himself up and returned to the Resistance, a cut on his right cheek and the injuries to his left temple and lower lip will remain visible. One of the official Funko Pop Poe Dameron characters even carries a scar on Poe’s right cheek. Similarly, Poe doesn’t appear in the second issue of the TFA comic, yet his face—eyes closed as he screams—takes up a great deal of the cover. Poe in danger and Poe hurt are also recurring motifs on covers for the Poe Dameron comic: the cover for issue #5 features Poe in binders, and the cover for issue #10 shows Poe bruised. Poe is thus a character often canonically in danger or pain.

The TFA transmedia universe similarly reinforces Poe’s body as a body in pain. In the Visual Dictionary, Poe’s entry includes a picture for a set of “First Order Binders” (12). Kylo Ren’s entry has a section entitled “Interrogation,” which includes an image of Ren questioning Poe (24). Perhaps nowhere, though, is a focus on torture more evident than in the children’s book Poe Dameron: Log Book. In it, classified First Order documents tell us “IT-000 unit XZ 1594 was instructed to use all available techniques to determine the location of a map the prisoner had” (63). After Poe refuses to answer the droid, “The IT unit repeated the question 813 times” and then “proceeded to apply methods 2265, 6304, 3333, and KB-A4 to the prisoner. The prisoner reacted violently to procedure KB-A4, and nearly swallowed his tongue. The IT unit increased the neuroshock amplitude and repeated the question” (63). Later, during Ren’s interrogation of Poe, “The prisoner’s scream was so voluminous that it shattered the IT-000’s sensory capsules” (63).

This is not to say that other characters aren’t injured or tortured in TFA and the texts that surround and inform it, but there is a difference. Desert scavenger Rey is also interrogated by Ren, but the lighting in her scene is much more even and bright. Rey also isn’t bloodied, and she resists Ren’s use of the Force and breaks herself out. Han Solo is killed at the end of the film, but there is no blood, and while Chewbacca is wounded, the wounds aren’t visible. Ren’s wound from Chewbacca’s bowcaster is similarly invisible—the only evidence of it is blood in the snow when Ren punches himself before his fight with Finn and Rey. The lightsaber gash to Ren’s face is also instantly cauterized. Finn is a bit bloodied in his fight with Ren, but his lightsaber wounds aren’t visible to the audience, either. While spaceships may explode and the Skywalkers’ limbs may be cut off, there is relatively little blood in the Star Wars cinematic universe. Yet, the only character who sustains clearly visible wounds that remain throughout TFA is Poe.

At first glance, these wounds might mark Poe’s failure in giving up information to Kylo Ren, yet Poe’s torture and wounding serve multiple narrative purposes, not the least of which is to set up both a censuring of Poe’s recklessness and a celebration of his masculine bravado. On one hand, Poe’s impulsiveness leads to him being captured. His resulting wounds thus work as a very visible condemnation of his behavior. He must be disciplined so that his recklessness can be checked—and the disciplining of Poe will most likely continue in Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017), as Oscar Isaac confirms that in that film, Leia “with tough love, wants to push Poe to be more than the badass pilot, to temper his heroic impulses with wisdom and clarity” (Locker).

However, Poe’s torture and wounding also serve to underscore his loyalty and how extraordinary he truly is. Describing the torture of Mel Gibson characters in films such as Braveheart (1995), Jeffrey A. Brown notes that the “violence suffered” by them “not only proves the superiority of their manliness but also sanctifies the supposedly higher moral value of that manliness. The Gibson protagonist suffers not just for himself but for a higher purpose” (137). Similarly, in TFA, Poe’s torture works not only to establish the depravity of the First Order—those who would use torture—but Poe’s devotion to his cause. In the midst of Ren’s questioning, Poe even spits out, “The Resistance will not be intimidated by you.” Therefore, while Poe does ultimately break under torture, he only does so once a Force-user probes his mind. At the beginning of the interrogation, Kylo Ren even remarks, “I’m impressed. No one has been able to get out of you what you did with the map.” Poe withstands other humans and interrogation droids; his failure at the hands of a Force-user, then, is only partial and in fact, ends up marking Poe as both tremendously dedicated and exceptional. As Peter Lehman observes, “In the cinema, a scar on a man’s face frequently enhances rather than detracts from his power, providing a sign that he has been tested in the violent and dangerous world of male action and has survived” (63). Taken this way, the torture is a test Poe doesn’t really fail—after all, he does not die; he rebounds and later hits back at the First Order. Furthermore, the torture and subsequent wounding prove Poe’s dedication and ability to withstand the kinds of pressure that would break a lesser man. Several fan works, however, question Poe’s ability to come out of his torture relatively unscathed.

Poe Dameron Hurts So Prettily

An Archive of Our Own (Ao3) is an online archive for fan works, and while Ao3 is not the only site where fans may upload work, it is one of the most popular. On the site, fans can post fan works that others can then access via tags—short descriptions of individual works. Tags might include what media text(s) a work is derived from, what characters appear in it, and other story or thematic elements. Searching through tags at Ao3 is not an exact science: fan works may be improperly tagged; tags can be misspelled, and any number of factors may keep a search from returning every relevant fan work. With that in mind, I draw my conclusions about Poe in fan works from my own anecdotal observations of work posted on Ao3, and as of September 25, 2017, there were 23,987 fan works posted in the TFA fandom on the site. Of those, 1,599 were tagged as h/c, accounting for around 6.6% of the total work produced in the fandom. Within the h/c tag, Poe Dameron is tagged in 685 works. The only character to be tagged more under the h/c tag is Armitage Hux, who is tagged 699 times. They both appear in about 43% of the fan works tagged as h/c.

An interesting thing happens, though, if one searches the TFA tags for “hurt” without comfort. This tag may appear in stories also tagged as h/c, but just searching “hurt” produces 245 works; of them, Poe is tagged in 166 or nearly 68% of the time. The next closest character is Finn with 120. If one searches the tag “torture,” 613 works in the TFA fandom are returned. Of those, Poe Dameron is again the most tagged character, appearing in 352 works or about 57% of the time. Although to be clear, this does not mean Poe is tortured in each of these works—only that he appears. The tag “Hurt Poe Dameron,” contains 118 works; while the similar tag “Hurt Kylo Ren” only has 24 works and “Hurt Finn” has 16. While these findings are far from scientific, there does seem to be a slight preference for hurting Poe (or at the very least aligning him with hurt) within a portion of the TFA works available on Ao3.

So, why all the hurting? For starters, the very premise of TFA—it takes place during a war and most characters are soldiers—feeds into the idea that characters will be injured. Also, fan works may simply be extending the TFA story: many Finn-centric h/c works focus on Finn’s recovery from his lightsaber wounds; others have him dealing with the psychological scars of being a former Stormtrooper. Similarly, many Poe-centric works examine his psychological trauma at having been tortured by Kylo Ren. Guatemalan-American actor Oscar Isaac plays Poe, and thus some fans suggest the propensity to hurt him in fan works may also play into racist stereotypes that shift suffering onto characters of color.

It also helps to look at the ways in which Poe lines up with some observations fans and scholars make about h/c more generally. Lorelei Jones suggests that the character being hurt “is always the character that is most openly emotional….” (“The Damsel in Distress Syndrome”). While Poe certainly fits those parameters, Finn does too, yet he isn’t tortured or hurt nearly as much in fan works. In “Why Does Obi-Wan Get All the Pain in TPM H/C Fic?” Alias Solo wonders if because Qui-Gon Jinn died in The Phantom Menace (1999), the fandom was reluctant to hurt him further. Applying this logic to TFA has some merit: the film ends with Finn in a coma, having survived a lightsaber slash to the back, and while many TFA fan works explore his coma and expected recovery, to some writers, it might be easier to hurt Poe because Finn suffers the more drastic injury.

Similarly, hurting Poe may stem from his canonical status as a dashing hero. The opening crawl to TFA identifies him as the Resistance’s “most daring pilot.” Star Wars Propaganda: A History of Persuasive Art in the Galaxy includes a poster showing Poe looking off into the distance with text that reads, “Watching Over The Skies and Stars” (Hildago, 104). The caption to the poster tells us “the joke among the Resistance pilots was that if Black Leader Poe Dameron posed for a poster, their numbers would skyrocket” and that the resulting prank poster “somehow saw dissemination on the HoloNet and prompted actual interest from would-be Resistance pilots” (104). Poe thus becomes a natural candidate for h/c in another way—unlike orphans Finn and Rey, his relative position as literal “Poster Boy of the Resistance” suggests he can survive being “knocked down a few pegs” without it seeming egregious. As tumblr user @sparxflame notes in discussing whump, which stands for h/c with a heavy emphasis on hurt:

When men in fiction do get hurt, they largely bounce back from it, action-hero style. You get this sort of ‘impervious, invulnerable man’ character, who never seems to experience any true sort of pain or suffering…There is, then, something appealing about…seeing the untouchable become touchable, the unhurtable become hurt, the invulnerable made vulnerable…seeing someone who usually shrugs off any kind of trauma or pain having to actually deal with that pain, and become vulnerable and more real as a result…

Yet, canonically, Poe’s torture and wounding seemingly make him vulnerable in ways other characters are not.

Thus, perhaps the most persuasive argument about why Poe is hurt is one made by @killian-whump on tumblr: “Characters who have a lot of vulnerable moments (both physical and emotional) during a show’s run tend to attract” h/c writers. There’s no denying the propensity to hurt Poe in the TFA transmedia universe, and there is even a tag on Ao3 called “Poe Dameron Hurts So Prettily.” It might seem like a joke at first, but thinking about the way the interrogation scene is structured, alongside the near fetishization of hurt Poe in other canonical works, and one might start to think Poe Dameron does in fact “hurt so prettily,” that hurting Poe in fan works is not simply a manifestation of fan desire but also a logical extension of what Poe faces in canon.

In his book Visible Fictions, John Ellis notes: “The fetishistic gaze is captivated by what it sees, does not wish to inquire further, to see more, to find out…The fetishistic look has much to do with display and the spectacular” (47). Poe’s torture in TFA is tailor-made for a fetishistic gaze, one that takes pleasure in the display of Poe’s wounds without much regard for how they were made nor how they will be healed: there is a certain to-be-looked-at-ness to Poe’s artful wounds. Yet, while there is certainly h/c that solicits a similar reader position, many h/c works promote more than a fetishistic gaze: taking pleasure in the spectacular ways Poe can be hurt, yes, but also delving deeper to get at both the bodily experience of Poe’s hurt and the physical and psychological aftermath of it. Poe may hurt prettily, but many fan works don’t simply leave it at that.

A Body of Consequence

On one hand, fans are reproducing Disney’s representation of Poe as canonically hurt, yet on the other hand, many h/c works challenge this representation—not so much by refusing to hurt Poe, but by insisting on filling in the narrative gaps produced by Poe’s torture and subsequent return to the Resistance. Tumblr user @thistlerosie reports a conversation with @coffeeinallcaps where the two acknowledge, “we feel bad about hurting Finn and Rey, but enjoy pummeling Poe” and @coffeeinallcaps believes this is because “there’s a missing element in Poe’s story arc…we see Poe go from broken to seemingly completely fine with no transitions. There’s something deeply unsatisfying about that…so we kind of need to recreate the pain, to break him again so we can build him back up and give him a complete arc” (qtd. in @deputychairman). Many critics and moviegoers have noted Poe’s absence during a great deal of the film is never adequately explained in TFA, and of all the major new characters, Poe has the least amount of screen time.

While some h/c works may simply be an excuse to give more “screen time” to a beloved character, others seem uncomfortable accepting the violence done to Poe in TFA wholesale, and these works aim to show the effects of this violence on Poe’s body and mind. In other words, while TFA may turn Poe’s suffering into fetishistic spectacle, several fan works want to recuperate that suffering by showing the repercussions of it. For example, in the second chapter of the fan work “Jump,” by Zoe_Dameron, Poe remembers his torture at the hands of Kylo Ren, and the chapter is littered with references to the realities of Poe’s physical pain: at one point, Poe feels his “eyes screwing shut as he shudders through what feels like a broken skull” and later, Poe will try “to focus on the words instead of the way his muscles are spasming futilely against the too-tight restraints, instead of the wound on his temple that has reopened and is bleeding anew, instead of the air that catches and stops in his throat.” Poe’s interrogation takes up over 1400 words of the 2064-word chapter, and whereas in the film, there were visible traces of what had been done to Poe, Zoe_Dameron details how those injuries feel: Poe’s torture is no longer merely spectacle but is made over as bodily experience.

Other works focus on the aftermath of Poe’s torture. In the_actual_letter_n’s “Cut it off or shut it down,” after the events of TFA, Poe is plagued by nightmares. When Finn confronts him about them, Poe’s “whole body tenses” but eventually Poe starts talking and his “voice trembles and he turns to the wall again, his breathing loud and ragged.” In beautifullights’ “can what is broken ever be repaired?” Poe tries to abandon the Resistance after his crash on Jakku because of his guilt at cracking during the interrogation. Trying to catch a ride to the Outer Rim, Poe confesses,

“I betrayed them. I was at that village. They captured me, tortured me. That was nothing. But then Kylo—” He can’t say the name. “He—I—he did something to me, something to my head, I—I couldn’t stop it. I broke. I betrayed the Resistance, gave them the information they wanted. This stormtrooper saved me, but—we crashed. He died. Now I’m alone. I can’t go back to the Resistance. Not now, not ever.” Poe finds himself crying, relief and pain all mixed together.

Here, fan writers insist on detailing likely reactions to trauma, refusing—as the film does—to act as if torture has no deeper impact than one’s skin.

In examining how Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009) dealt with the injuries sustained by Captain Kara “Starbuck” Thrace, Sarah Hagelin notes “the show treats her physical injuries as difficulties to be soldiered through, not as debilitating traumas” (126). One could argue that Disney and Lucasfilm do the same with Poe’s injuries—they are there to mark him as resilient and newly disciplined, yet they do not indicate any real trauma. Suzette Chan argues that on the television show Supernatural (2005- ), a show that is constantly hurting its two main characters both psychologically and physically, “The show resolves the tension between marketability and storytelling by making scars disappear and wounds invisible” (1.4). While the show allows the Winchester brothers enough space to brood about their psychological scars, their physical scars tend to fade quickly. As a result, Chan notes “many fan writers give Sam and Dean bodies of consequence, bodies that bear the scars of the past” (1.5). In TFA and its expanded transmedia universe, I would argue that Disney superficially provides Poe with a body of consequence—rendering Poe’s scars visible is an essential element to making sure audiences read him as both reckless and devoted to the cause. Poe is set up as willing to sacrifice himself for the Resistance, and his body bears the brunt of that willingness. Yet, within the film itself, while Poe’s hurt is eroticized—to the point that he “hurts so prettily”—any repercussions of that hurt happen off screen, if they happen at all. Poe is tortured and crashes and then appears on D’Qar ready to fight. There are lingering physical traces of his past hurt, but no sense of how—or even if—he was able to put himself back together again. Some h/c may be filling in that gap.

I am not arguing that all h/c featuring Poe fills that gap; yet, it does explain one reason why there might be a slightly stronger tendency towards hurting Poe than other TFA characters in fan works. Moreover, while the canonical tendency to hurt Poe serves the purpose of setting him up as a leader-in-training, taming his wild ways so he can rise in the ranks of the Resistance and reassert his extraordinary ability to endure, fan works complicate this characterization by problematizing the heroic aura of torture. In her seminal work on the male action heroes of the 1980s and ‘90s, Susan Jeffords notes that the torture of these hard-body heroes often worked to distance these heroes from the audience: “Those who could fantasize easily about replicating Rambo’s assaults on tanks, rescues of prisoners, or uses of weapons seemed now to have difficulty imagining suturing or cauterizing gaping wounds in their own bodies” (49). The torture Jeffords describes proved how separate these heroes were from the ordinary, everyday people watching them.

Yet, some fan works opt to move beyond highly aestheticized torture, not by necessarily rejecting it, but rather by adding to it, deepening it, and making it much more visceral. Hence, the pain becomes much more pronounced and the psychological scars linger long after the physical ones have faded. Moreover, these fan works critically reassess narratives of male bravado that would celebrate the spectacle of torture as a rite of heroism, insisting instead on highlighting the realities of pain and torture. In many ways, they are reclaiming this torture to bring it back into the province of ordinary, everyday people, closing the gap between Poe and his audience. While this may not destabilize Poe’s canon characterization, it nevertheless works to resist a narrative universe that would provide violence without consequences.

Works Cited

Alias Solo. “Why does Obi-Wan get all the pain in TPM h/c fic?” The Fanfic Symposium, Dec. 14, 1999, http://www.trickster.org/symposium/symp40.htm. Accessed 2 Nov. 2016.

@artisfaction. Untitled Blog Post. Artisfaction’s Tumblr blog, 24 March 2016, http://artisfaction.tumblr.com/post/141622781177. Accessed 19 Aug. 2016.

Ayers, Drew. “Bodies, Bullets, and Bad Guys: Elements of the Hardbody Film.” Film Criticism, vol. 32, no. 3, 2008, pp. 41-67.

Bacon-Smith, Camille. Enterprising Women: Television Fandom and the Creation of Popular Myth. U of Pennsylvania P, 1992.

beautifullights. “can what is broken ever be repaired?” An Archive of Our Own, 18 Jan. 2016, http://archiveofourown.org/works/5670289/chapters/13062367. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Castellucci, Cecil and Jason Fry. Journey to Star Wars: The Force Awakens: Moving Target: A Princess Leia Adventure. Disney Lucasfilm Press, 2015.

Chan, Suzette. “Supernatural bodies: Writing subjugation and resistance onto Sam and Dean Winchester.” Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 4, 2010, http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/179/160. Accessed 2 Nov. 2016.

@deputychairman. Untitled Blog Post. Deputychairman’s Tumblr blog, April 2016,

http://deputychairman.tumblr.com/post/143637708363/thistlerosie-coffeeinallcaps-this-is-a-very-good. Accessed 19 Aug. 2016.

Edwards, Tim. “Spectacular Pain: Masculinity, Masochism and Men in the Movies.” Sex, Violence and the Body: The Erotics of Wounding, edited by Viv Burr and Jeff Hearn, Palgrave MacMillan, 2008, pp. 157-176.

Ellis, John. Visible Fictions: Cinema, Television, Video. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982.

Fathallah, Judith May. “H/c and me: An autoethnographic account of a troubled love affair.” Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 7, 2011, http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/252/206. Accessed 2 Nov. 2016.

Foster, Alan Dean. Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Del Rey, 2015.

Gillam, Lucy. “We Always Hurt the Ones We Love.” The Fanfic Symposium, Nov. 1, 1999, http://www.trickster.org/symposium/symp13.htm. Accessed 2 Nov. 2016.

Hildago, Pablo. Star Wars: Propoganda: A History of Persuasive Art in the Galaxy. Harper Design, 2016.

Hildago, Pablo. Star Wars: The Force Awakens: The Visual Dictionary. DK Publishing, 2015.

“Hurt/Comfort.” Fanlore, 9 Sept. 2016, http://fanlore.org/wiki/Hurt/Comfort. Accessed 20 Nov. 2016.

Jeffords, Susan. Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era. Rutgers UP, 1994.

Jones, Lorelei. “The Damsel in Distress Syndrome.” The Fanfic Symposium, Nov. 17, 1999, http://www.trickster.org/symposium/symp24.htm. Accessed 2 Nov. 2016

@killian-whump. Untitled Blog Post. Killian-Whump’s Tumblr Blog, Sept. 2016,

http://killian-whump.tumblr.com/post/150458835173/frenchpichux-tlynnwords-okay-guys-i-am. Accessed 10 Nov. 2016.

Kogge, Michael. Poe Dameron: Flight Log. Studio Fun, 2016.

Lehman, Peter. Running Scared: Masculinity and the Representation of the Male Body. Temple UP, 1992.

Linn, Rachel. “Bodies in horrifying hurt/comfort fan fiction: Paying the toll.” Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 25, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2017.1102. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Locker, Melissa. “Star Wars’ Oscar Issac Just Said the Sweetest Thing About Princess Leia.” Time.com, Aug. 11, 2017, http://time.com/4897076/star-wars-the-last-jedi-hint-oscar-isaac/. Accessed Sept. 25, 2017.

Mayhew, Mike, cover artist. Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Written by Chuck Wendig. No. 2, Marvel, 2016. StarWars.com, http://www.starwars.com/news/comic-book-galaxy-star-wars-the-force-awakens-2-and-more.

“Poe Dameron.” Wookieepedia: The Star Wars Wiki, http://starwars.wikia.com/wiki/Poe_Dameron. Accessed 20 Nov. 2016.

Renae. “Hurt/Comfort: a Confession and a Celebration.” The Fanfic Symposium, July 5, 2000, http://www.trickster.org/symposium/symp55.html. Accessed 2 Nov. 2016.

Rucka, Greg. Star Wars: Before the Awakening. Disney Lucasfilm Press, 2015.

Secrets of The Force Awakens: A Cinematic Journey. Directed by Laurent Bouzereau. Lucasfilm, 2016.

Seitz, Dan. “Here’s the Surprising Way Oscar Isaac Saved Poe Dameron From Death in ‘Star Wars: The Force Awakens’.” Uproxx: GammaSquad, March 31, 2016, http://uproxx.com/gammasquad/star-wars-oscar-isaac-poe-dameron-death/. Accessed 18 Jan. 2017.

Soule, Charles (w) and Noto, Phil (p & i). Poe Dameron #1, April 2016.

Soule, Charles (w) and Noto, Phil (p & i). Poe Dameron #5, Aug. 2016.

Soule, Charles (w) and Noto, Phil (p & i). Poe Dameron #10, Jan. 2017.

@sparxflame. Response to anonymous ask. Sparxflame’s Tumblr Blog (The Bookshop), Jan. 2017, http://sparxwrites.tumblr.com/post/155402264433/i-think-u-have-a-point-abt-kinks-being-only-one. Accessed 18 Jan. 2017.

Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Directed by J.J. Abrams, performances by Daisy Ridley, John Boyega, and Oscar Isaac, Lucasfilm, 2015.

the_actual_letter_n. “Cut it off or shut it down.” An Archive of Our Own, 27 Dec. 2015, http://archiveofourown.org/works/5546978. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Wendig, Chuck (w), Ross, Luke (p), and Martin, Frank (i). Star Wars: The Force Awakens #1, June 2016.

Wendig, Chuck (w), Ross, Luke (p), and Martin, Frank (i). Star Wars: The Force Awakens #2, July 2016.

Winters, Sarah Fiona. “Vidding and the perversity of critical pleasure: Sex, violence, and voyeurism in ‘Closer’ and ‘On the Prowl’.” Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 9, 2012, http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/292/297. Accessed 2 Nov. 2016.

Zoe_Dameron. “Jump” (Chapter 2). An Archive of Our Own, 19 Sept. 2017, https://archiveofourown.org/works/12129747/chapters/27537093. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Back to Issue 12 Table of Contents